The Motorcycle as Art

by David Russell #832

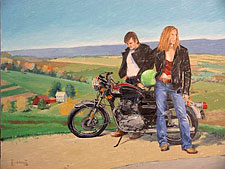

Recently, while returning home from a business trip, I decided to take the long way home and visit my favorite art museum. One special exhibit at the museum were two collections of drawings and paintings—the first was an expansive collection of Andrew Wyeth watercolors, while the second consisted of a compilation of landscape paintings by a turn of the century painter whose name already escapes me. His art depicted scenes from his travels that included vast forests, rivers, deserts, and American mountains from 100 years ago. The paintings were gorgeous, magnificently-breathtaking pieces of work. Standing in front of a painting representing a hillside farm overlooking a river on a sunny day, I mentally caught my breath and listened to my subconscious exclaim, "This is beautiful. Just like a motorcycle is beautiful." This may sound slightly weird, I realize but at that moment this thought was a perfect, pristine truth. Both the painting and the motorcycle I had considered were beautiful works of art created by gifted mortals—one painted a century before, the other designed and assembled in Europe decades ago. Both are beautiful to behold, perfect in their design, form and execution.

Before I lead you seemingly altogether off the deep end of my artistic musings, let me establish two points. First, I would describe myself as an Artist. I arrive at this conclusion through no particular sense of grand destiny or especially inflated ego, but merely because of the logic that I make money producing work that my clients refer to as "art" on their check stubs. This, combined with the fact that I paid out perfectly good money to go to Art School, leads me to the inescapable truth that I must be an Artist. Hard to believe because I am not in an alternative-music rock-n-roll band; nor have I ever smeared chocolate on my naked body in front of a paying audience; nor did I receive any NEA funding to help me insult your religious beliefs; and, finally, I am often accused of not being sensitive. Before I lead you seemingly altogether off the deep end of my artistic musings, let me establish two points. First, I would describe myself as an Artist. I arrive at this conclusion through no particular sense of grand destiny or especially inflated ego, but merely because of the logic that I make money producing work that my clients refer to as "art" on their check stubs. This, combined with the fact that I paid out perfectly good money to go to Art School, leads me to the inescapable truth that I must be an Artist. Hard to believe because I am not in an alternative-music rock-n-roll band; nor have I ever smeared chocolate on my naked body in front of a paying audience; nor did I receive any NEA funding to help me insult your religious beliefs; and, finally, I am often accused of not being sensitive.

The second point I wish to make is that I love motorcycles. From my first Japanese trail bike that I still have tucked away in a corner of the basement, to my first restoration (a BSA single bought for the price of a Harley carburetor from a desperate friend), to all the other machines that have come to my house to visit or permanently reside. I have always loved motorcycles—not necessarily for their riding qualities, either, since many of mine are never actually started. I’ve loved and appreciated them for some other reason; a reason I hope goes beyond mere materialism, or junk collecting, or that basic American need to consume far more than we need. I have come to believe that motorcycles represent Art.

What then is Art? Much like the terms "love" and "low mileage", art’s meaning seems to be commonly corrupted. The dictionary defines art as, among other things, the "quality, production, expression, or realm of what is beautiful." Going beyond this definition, I’d say that art is created to achieve one or both of the following purposes: (1) to synthesize or reinterpret natural beauty, and (2) to express an idea. In my personal opinion, truly great art achieves both of these ends. Let’s take these two purposes and look at them one at a time.

The first—"to synthesize or reinterpret natural beauty", might be thought about in the following terms. First, I’ll describe natural beauty as the naturally-existing universe of form, pattern, shape, and movement that is pleasing to us. We did not invent this beauty; it was all present before we existed. We are free, though, to reinterpret it; not to necessarily improve upon it, but to change the make-up, perhaps to compress, delete, add or expand upon it. Donatello’s revolutionary sculptures of the 1500s expand and permanently capture a glimpse of the beautiful lines and forms of the human body, while prehistoric cave artists reduced these same forms to the simplest possible abstractions. Mozart didn’t invent the tones that he used in his compositions; he simplified them, wove them, expanded them, and gave mathematical structure to the very same notes that the birds sang outside his window. In fact, Mozart’s techniques in this way are very much like what Eric Clapton does today with his electric guitar. So what does this have to do with the ’69 Triumph in my garage, you ask? More than you can imagine. The motorcycle is a symphony; a wonderful mural of line, shape and form embellished with color and texture. As I disassembled by first restoration project BSA, I was surprised at the inherent beauty of the machine. The design of the carburetor; the glimmer of the brass against alloy, of rubber against steel, all amazed me. The way the lines of the gas tank picked up the silhouette of the engine finning; the way each little curve and corner and edge and shape seemed so perfectly designed by engineers and assembled purposely by line workers astounded me.

But, one might ask, doesn’t the fact that the motorcycle is designed to be functional—to do something—negate much of this beauty? I’d answer a resounding No! Frank Lloyd Wright, the father and patron saint of modern architecture, is well-known for his belief that "form follows function." The hammer looks the way it does because of what it does—if a hammer looked like a pillow, it wouldn’t be a very good hammer. A motorcycle, likewise, looks like a motorcycle because of what it does. Wright insisted upon the design of his structures being beautiful, no matter how functional they had to be. Consider the immense diversity among functional objects, among motorcycles in particular. Both Edward Turner’s Triumph Speed Twin and A.A. Scott’s watercooled 2-strokes had wheels and an engine, but consider how wonderfully and successfully different in execution each is. Many enthusiasts find racing motorcycles to be particularly attractive as objects of art. The stark functionality and the powerful intent of the designer to make the machine as light and as efficient as possible resulted in the racing machine being more than a mere abstract vision of the designer’s intent. Whatever a 1920s Indian board track racer or a 1960s CZ motocrosser lacks in paintwork and chrome, they more than make up for in uninterrupted beauty of line and form. Of course, there is much to appreciate in the gloriously decorated street machines of yesterday and today, too. The subtle colors, the contrast of metals, the intricate shapes of horns, the switches, the decals, the emblems—all give such machines immense and lasting visual appeal. But, one might ask, doesn’t the fact that the motorcycle is designed to be functional—to do something—negate much of this beauty? I’d answer a resounding No! Frank Lloyd Wright, the father and patron saint of modern architecture, is well-known for his belief that "form follows function." The hammer looks the way it does because of what it does—if a hammer looked like a pillow, it wouldn’t be a very good hammer. A motorcycle, likewise, looks like a motorcycle because of what it does. Wright insisted upon the design of his structures being beautiful, no matter how functional they had to be. Consider the immense diversity among functional objects, among motorcycles in particular. Both Edward Turner’s Triumph Speed Twin and A.A. Scott’s watercooled 2-strokes had wheels and an engine, but consider how wonderfully and successfully different in execution each is. Many enthusiasts find racing motorcycles to be particularly attractive as objects of art. The stark functionality and the powerful intent of the designer to make the machine as light and as efficient as possible resulted in the racing machine being more than a mere abstract vision of the designer’s intent. Whatever a 1920s Indian board track racer or a 1960s CZ motocrosser lacks in paintwork and chrome, they more than make up for in uninterrupted beauty of line and form. Of course, there is much to appreciate in the gloriously decorated street machines of yesterday and today, too. The subtle colors, the contrast of metals, the intricate shapes of horns, the switches, the decals, the emblems—all give such machines immense and lasting visual appeal.

The second purpose of art is "the expression of an idea". Formerly held in equal standing with the beautiful purpose of art, "idea" has come to be the driving force in modern art, especially since the turn of the last century. Michaelangelo’s "David" expresses the ideas of strength and the physical grace of man in God’s image. In a more modern perspective, the welded rusty car parts on the lawn of your local library may have a lot to say about the decline of Western culture—representing an idea—yet be practically void of any aspect of beauty. Likewise, well-known pop-art works like Andy Warhol’s "Campbell’s Soup Can" or "Marilyn Monroe" silk-screens also are heavy on idea, but light on beauty and skill of execution. The second purpose of art is "the expression of an idea". Formerly held in equal standing with the beautiful purpose of art, "idea" has come to be the driving force in modern art, especially since the turn of the last century. Michaelangelo’s "David" expresses the ideas of strength and the physical grace of man in God’s image. In a more modern perspective, the welded rusty car parts on the lawn of your local library may have a lot to say about the decline of Western culture—representing an idea—yet be practically void of any aspect of beauty. Likewise, well-known pop-art works like Andy Warhol’s "Campbell’s Soup Can" or "Marilyn Monroe" silk-screens also are heavy on idea, but light on beauty and skill of execution.

When we admire motorcycles, we are perceiving several ideas. The most obvious may be ideas relating to speed and freedom—the perfect execution of form following function. Perhaps idea is also evident in the finishing of the machine—the Spartan, serious look of an early racing bike, or the sensual feel of an Italian sport bike. Another form of idea that I particularly enjoy in motorcycles is what you may call the "ethnic origin" idea; that where the machine comes from greatly influences its performance and its look. For example, I see character in the BSAs and Triumphs that is unmistakably British. A proper, distinguished British pose is evident, which at the same time encompasses some of the oddest little idiosyncrasies such as the Amal carbs, the Lucas electronics, the fragile bits and pieces that together form such a noble--if just a bit silly--presence. My Spanish motorcycles are very different. They are hot-blooded, dark-skinned, emotional temptresses which belong under a hot Mediterranean sun and conjure up images of bullfights and civil war. My German MAICOs are again entirely the opposite. Stark, functional, Teutonic war-horses with no nonsense added. Even the coffin-shaped fuel tank has rough, non-rounded edges. Then, consider the Harley-Davidson—big, corn-fed and Midwestern, with massive cylinders that feed on massive quantities of [formerly] cheap gas. These machines are loud, free, excessive and bred from the spirit that crossed the Atlantic in little wooden ships in the 18th century, rolled over a continent in the 19th century, and popped open a beer to think about it in the 20th century. These motorcycles are happy—retaining a bit of roughness and edge—but happy nonetheless to be alive and to roar across the horizon on warm summer evenings.

The question, then, is Why do we love old motorcycles so much? There are many reasons. The thrill of riding a machine with a feel and a personality, a time passage back to our youths, a recollection of times long gone but still loved, and their value as artwork created by gifted designers and builders; all of these are reasons we love these objects.

I am often kidded for my habit of acquiring old machines, restoring them, and then basically letting them sit while I admire them. I’ve become a standing joke with my wife for being found in the garage, sitting quietly on a stool just looking at a motorcycle. Now, I have come to realize this is very politically incorrect among some of my fellows. It is much more correct—as I hear it—to put these machines back on the road where they should be. Let me state in my defense, however, that I am not a filthy-rich hoarder of gallant, red-blooded motorcycles scooped-up from the family farm in Iowa, nor do I conspire to lock up as many of these machines as possible in a dark warehouse somewhere in the most sin-ridden corner of Las Vegas, while all the while plotting to sell them to the highest-bidding godless foreigner at first opportunity. I love these old bikes. I take pride in saving many of them from rusting into oblivion, and I love to share them with my friends. Am I going to ride them? Well, as soon as I get the paint just right, and obtain the final ignition set on earth from Tajikistan…or was it Mozambique? What I am proposing is that these motorcycles are my—and your—art collection. We may not be able to obtain great paintings by old masters, but we can still obtain some of the most beautiful objects ever produced by man. Furthermore, we have very valid reasons for desiring to surround ourselves with these machines—reasons more substantial than simple materialism or profit potential. How fortunate that I, like you, am lucky enough to be able to

savor and enjoy these old machines. How fortunate we are to look forward to granting others the same gift now and in the future. savor and enjoy these old machines. How fortunate we are to look forward to granting others the same gift now and in the future.

Now…would anyone have a solid lead on a non-running, mid-70s 125 MAICO for a conscientious art collector? Just thought I’d ask.

Cheers,

David

***

|